Sadō (Japanese tea ceremony) is drawing attention from around the world as a cultural tradition that embodies Japan’s unique sense of beauty and spirituality.

This article provides a detailed historical overview—from tea’s introduction to Japan during the Nara period (710–794), through Sen no Rikyū’s refinement of the ceremony, up to the present day. Understanding the evolution of the tea ceremony reveals the depth of Japanese culture and highlights its enduring spiritual values.

- Origin and early introduction of the tea ceremony

- Turning point during the Kamakura period (1185–1333)

- Muromachi (1336–1573) and Sengoku (c. 1467–1603) period developments

- Edo period (1603–1868) and the rise of schools

- Modern tea history and changes

- Meaning and practical values of tea ceremony

- Steps and basic flow of the tea ceremony

- Summary

Origin and early introduction of the tea ceremony

The history of the tea ceremony began when tea was brought from China to Japan. The tea culture of that era was markedly different from the tea ceremony practiced today.

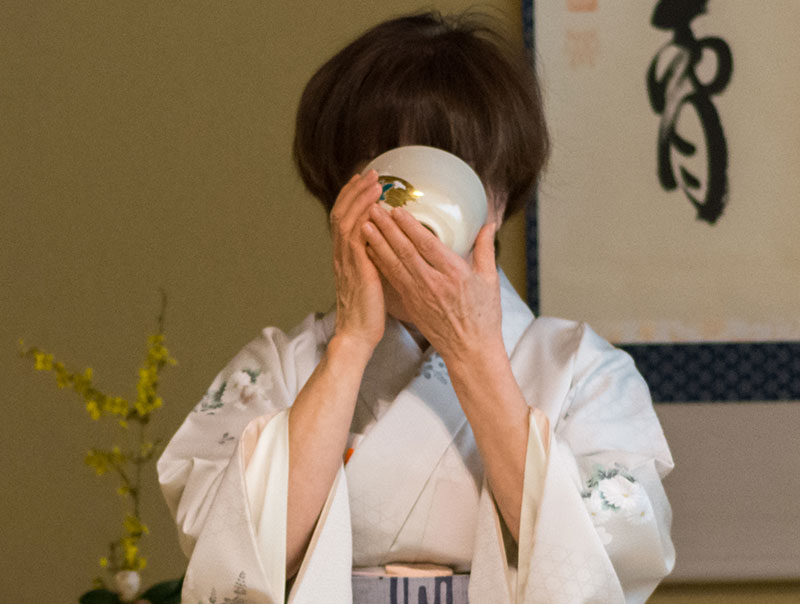

Photo for illustrative purposes

Tea culture in the Nara and Heian (794–1185) periods

There are various theories, but it’s believed that systematic tea knowledge first arrived in Japan from China between the Nara and Heian periods. The Chajing (known as The Classic of Tea in English), written by China’s Lu Yu, introduced cultivation, harvesting, preparation, and drinking methods for tea.

The earliest known record of tea consumption in Japan appears in the Nihon Kōki, which states that in 815 a monk named Eichū served tea to Emperor Saga. At that time, tea came in compressed, steamed cakes called danchá, brought by envoys to Tang China or by monk-students studying abroad.

At first, tea was used medicinally and in Buddhist rituals, and was consumed only by the noble and monastic classes.

Characteristics of early tea culture

Tea culture in the Heian era was heavily influenced by China, with little uniquely Japanese development yet. Tea plants were grown mainly around temples, and utensils and methods resembled Chinese prototypes.

Turning point during the Kamakura period (1185–1333)

The Kamakura period marked a major turning point in tea history. It was during this time that tea became closely linked with Zen Buddhism, laying the foundations for the modern ceremony.

Photo for illustrative purposes

Eisai’s promotion of powdered tea

In 1191, the Zen monk Eisai brought the custom of matcha (whisked tea) from the Song dynasty to Japan. Eisai planted tea seeds in the garden of Ishigami-bō at Reisen-ji Temple in Higashi-Sefuri village (present-day Yoshinogari town), Saga Prefecture, and this became the foundation for the popularization of tea cultivation for matcha in Japan.

Eisai didn’t just introduce whisked tea; he wrote the Kissa Yōjōki, systematically documenting tea’s benefits and how to serve it. Zen temples became centers for this tea culture, elevating tea as a tool for spiritual discipline—a foundation for the later tea ceremony.

The expansion of tea cultivation and the origins of Uji tea

During this era, tea cultivation expanded across Japan. Of particular importance was Master Myōe, who planted the first tea seeds in Uji, laying the groundwork for Uji’s future reputation as a tea-culture center.

Towards the late Kamakura period, tea gatherings like the “Four Heads Tea Gatherings” began, giving tea a social and cultural dimension beyond simple consumption.

Muromachi (1336–1573) and Sengoku (c. 1467–1603) period developments

From the Muromachi to the Sengoku era, the tea ceremony underwent major transformation. The core philosophies and format that define it today were established during this time.

Photo for illustrative purposes

Murata Jukō’s creation of wabi-cha

In mid-Muromachi, Murata Jukō revolutionized tea culture by introducing the concept of wabi-cha, emphasizing quiet simplicity instead of lavishness. He used everyday Japanese tools, not luxury imports, shifting focus from material to spiritual richness. This philosophy—valuing simplicity over material extravagance—deeply influenced Sen no Rikyū later on.

Takeno Jōō’s refinement of the ceremony

Takeno Jōō, a student of Jukō’s grandson, further refined the wabi-cha spirit, bringing stricter aesthetic standards to tea rooms and utensils. He helped formalize the relationship between host and guest. The foundational forms he established endured to the present day.

Sen no Rikyū’s completion of the tea ceremony

Among the most significant historical figures in tea history is Sen no Rikyū. Building on Jukō and Jōō’s traditions, Rikyū perfected a uniquely Japanese tea ceremony grounded in the principles of wakei seijaku. He innovated in tea room design, utensil selection, and serving procedures.

The form of serving a single bowl of tea with heartfelt hospitality—prepared by the host—was solidified by Rikyū and remains central today.

Edo period (1603–1868) and the rise of schools

During the Edo era, tea ceremony became more accessible and diverse schools emerged. Tea culture spread from samurai to commoners.

Photo for illustrative purposes

Establishment and growth of the three Sen families

In early Edo, the three Sen families—Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushakōjisenke—formed, carrying on Rikyū’s lineage. They formalized teaching methods and succession systems. Institutionalizing the iemoto system (a traditional grand master system responsible for preserving the school’s lineage and authority) allowed tea to spread nationwide.

Spread among samurai as a cultural practice

By mid-Edo, tea ceremony was integral to samurai education—not just a pastime, but vital for character development and social grace. Terms like “sukidō” (roughly, “the way of refined taste”) and “otemae” (the formal procedure of preparing tea) arose, capturing ceremony’s artistry. Emphasis on spiritual growth and Zen continued.

Popularization among townspeople and commercialization

Later Edo saw tea ceremony embraced by commoners, bringing commercial growth. Utensil production, sales, and private tea events flourished, creating a tea economy.

Modern tea history and changes

Since the Meiji Restoration, tea ceremony has faced major shifts—initial decline under Western influence, then revival, continuing into today.

Photo for illustrative purposes

Crisis after the Meiji Restoration (1868)

The Meiji era’s rapid Westernization threatened tea ceremony’s survival. Viewed by some as outdated, it faced existential challenge.

Yet practitioners redefined its value, reasserting its aesthetics and spiritual depth as essential Japanese cultural assets, leading to preservation efforts.

Ties to women’s education

Mid-Meiji saw tea ceremony adopted in women’s educational institutions. This shift made tea ceremony widespread in ordinary households, laying foundations of modern culture.

Postwar recovery and globalization

After WWII, tea ceremony recovered and took on national cultural significance. From the 1960s, it became globally recognized through overseas exhibitions and instruction. Today it’s practiced and taught worldwide.

Meaning and practical values of tea ceremony

Tea ceremony is not just about tea—it is a holistic art form with deep spiritual and practical significance. Let’s explore why it remains beloved today.

Photo for illustrative purposes

The spiritual ideals of wakei seijaku

The core principle—“wakei seijaku”—remains highly relevant today. Wa signifies harmony between people and nature; kei, mutual respect; sei, purity of heart and environment; jaku, inner calm. These ideals offer practical solutions for mental peace and better relationships in today’s stressful society.

The meaning of ichigo ichie

The concept of “ichigo ichie” reminds us to cherish the unique, non-repeatable moment of any meeting. It encourages deeper connections and mindfulness, bringing benefits to both daily life and professional interactions.

Steps and basic flow of the tea ceremony

The practice of tea involves prescribed steps and procedures refined over centuries.

Photo for illustrative purposes

Preparation and invitations

Formal tea gatherings begin with sending invitations. Guests respond politely and prepare accordingly. For the host, preparing the tea room and garden is an essential part of setting the stage.

Decor reflects the season; flowers and scents are subtle. Stone placement in the garden guides guests quietly toward the tea room.

Entering the tea room and seating

Guests enter through the low nijiriguchi, bowing to show humility and equality. The main guest (shōkyaku) sits near the alcove, followed by others. Correct posture and behavior help create an atmosphere of calm and concentration.

Utensils and the serving procedure

Each tool—the scoop, whisk, bowl—holds meaning and tradition in its design. Though styles differ by school, the typical sequence remains: warm the bowl, add powdered tea, pour hot water, whisk, and present. Every movement is graceful.

Drinking tea and utensil appreciation

Sweets are served before tea to balance bitterness. When offered the bowl, guests receive it politely, rotate it, sip slowly, wipe the rim, and bow with gratitude. At the end, they inspect the utensils, appreciating their craftsmanship as objects of art.

Summary

The history of tea, from its introduction in the Nara era to modern-day practice, spans some 1,200 years. Through changing eras and contexts, its core spiritual values endure.

Photo for illustrative purposes

- Tea introduced during the Nara–Heian period; initially used for medicine and Buddhist rituals

- In Kamakura, Eisai brought powdered tea and strengthened Zen ties

- Murata Jūko, Takeno Jōō, and Sen no Rikyū refined the tea ceremony into what we know today

- In Edo, the Three Sen families formed and the ceremony spread across social classes

- From Meiji onward, women’s schools made tea part of daily life, and postwar efforts globalized it

By studying tea’s history, we can appreciate Japanese culture’s deep spirituality and aesthetics. Experience it firsthand to truly understand its depth.