Ukiyo-e (traditional Japanese woodblock prints) is a style of painting that vividly reflected the everyday culture of commoners during Japan’s Edo period (1603 to 1868).

What began as a popular art form embraced by the masses eventually crossed borders, gaining worldwide acclaim and recognition as a highly valued art.

In this article, we’ll explore the history and diverse genres of ukiyo-e, as well as the works of its most famous masters, to uncover the unique appeal and cultural background of this art form.

The allure of ukiyo-e and its historical backround

Ukiyo-e was born in the late 17th century, during the early Edo period.

One of the pioneering artists of this era was Hishikawa Moronobu, best known for his work “Beauty Looking Back.”

Unlike the mainstream at the time—one-of-a-kind hand-painted works—he advanced ukiyo-e by adopting the woodblock printing technique, which made it possible to produce multiple copies at once and at a more accessible price.

By lowering costs, art shifted from something exclusive to the upper classes into an affordable medium that common people could enjoy.

This accessibility allowed ukiyo-e to spread rapidly among the populace, establishing itself as a central medium of popular culture.

Commoner culture and the birth of ukiyo-e in the Edo Period

At the time, ukiyo-e circulated less as fine art and more as a form of publication, making it a familiar item in the daily lives of ordinary people.

For instance, in genres such as bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women) and yakusha-e (actor prints), many works depicted famous kabuki actors and celebrated women of the towns.

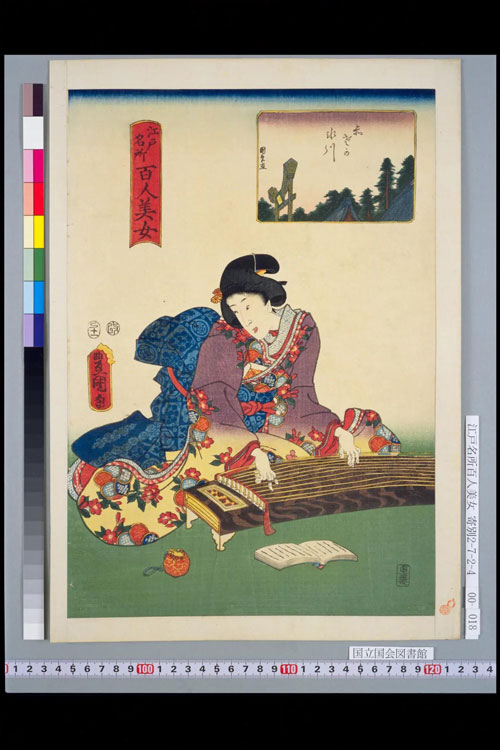

Kunisada Utagawa (Utagawa Toyokuni III), “Akasaka Hikawa (One Hundred Beautiful Women of Edo)” / Source: National Diet Library “NDL Image Bank”

These prints were much like modern-day bromides (celebrity photo cards), which people enjoyed by choosing their favorites, displaying them at home, or using them as conversation pieces with friends.

Ukiyo-e was also closely tied to everyday items.

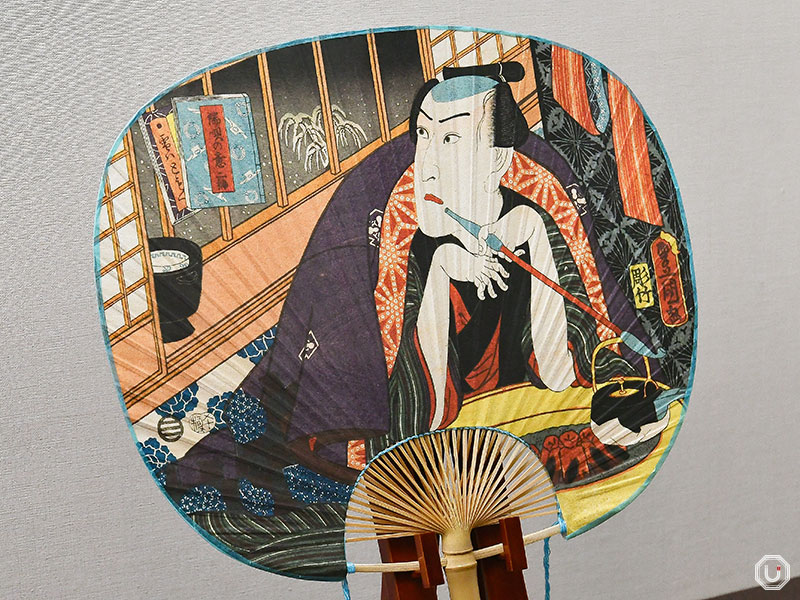

At Ibasen, a long-established shop founded in 1590, ukiyo-e designs were used on fans and uchiwa (round fans), bringing seasonal patterns into daily life and becoming part of the culture of ordinary people.

These designs were not only for viewing but were also enjoyed in a more personal, wearable sense.

Ukiyo-e for uchiwa fans (uchiwa-e) and folding fans (ōgi-e) on display at the Ibasen Ukiyo-e Museum

Moreover, ukiyo-e in the Edo period was not simply an object of appreciation as it is today.

People would decipher hidden hints and symbols in the artwork, or gossip about the actors’ love affairs and backstage stories depicted, making ukiyo-e one of the popular forms of entertainment and conversation starters of the time.

In other words, ukiyo-e was a cultural convergence nurtured within the city of Edo, shaped through the eyes and lives of its people.

It was a medium of information, a part of daily life, and a form of entertainment—a truly multifaceted presence.

The difference between ukiyo-e paintings and woodblock prints

Ukiyo-e can be broadly divided into two types: woodblock prints and hand-painted works.

What truly allowed ukiyo-e to flourish during the Edo period was the emergence of the woodblock printing technique.

So, what exactly distinguishes these two types?

| Woodblock prints | Hand-painted works | |

|---|---|---|

| Production method | Based on a draft sketch, the design is carved into wooden blocks, then printed onto washi paper with different blocks for each color | Painted directly by the artist with a brush |

| Reproducibility | Multiple copies can be produced as long as the woodblocks exist | One-of-a-kind work |

| Characteristics | Created through multiple stages with division of labor; the same design can be widely circulated | Original works that reflect the artist’s individual brushwork |

Most ukiyo-e artists did not limit themselves exclusively to either woodblock prints or hand-painted works.

Famous artists such as Katsushika Hokusai and Kawanabe Kyōsai focused on hand-painted works in their later years, and their surviving pieces are highly valued for their refined brushwork.

Hand-painted ukiyo-e left behind by artists can be viewed in museums, the most famous being the Ōta Memorial Museum of Art in Harajuku, Tokyo.

This museum specializes in ukiyo-e and has even hosted exhibitions dedicated to masterpieces of hand-painted works.

What is ukiyo-e?

The word ukiyo, which gave ukiyo-e its name, was originally written as 憂世 (ukiyo).

Here, the character 憂 (corresponding to uki in ukiyo) means worry, anxiety, or suffering and it is tied to 世, meaning “world.” In other words, ukiyo once described “a world full of hardships,” “a fleeting, inescapable present”—a pessimistic view of life.

However, with the arrival of the Edo period, its meaning shifted dramatically.

As townspeople began to gain economic power and build their own livelihoods, they embraced a new outlook on life: “to enjoy this world while living in it.”

Within the culture of Edo, the nuance of “a world of pleasure” or “a life lived in merriment” grew stronger, and the character 浮 (also pronounced “uki” and meaning “floating”) came to be used instead, the new combination 浮世 meaning “floating world.”

Thus, ukiyo was more than just a linguistic shift—it reflected the outlook of Edo townspeople and the values of the age. And it was this ukiyo that ukiyo-e would later visually portray.

Packed with trends, fashions, and amusements, ukiyo-e captured the very essence of urban culture at the time—preserving the spirit of the “floating world” on paper.

What is the history of ukiyo-e?

Ukiyo-e is known for its distinctive compositions, vivid colors, and depictions of everyday life among commoners. Yet, the term covers a wide range of genres.

Let’s take a look at some of the most representative categories of ukiyo-e.

Bijin-ga

No discussion of ukiyo-e is complete without bijin-ga, or “pictures of beautiful women.” These works often depicted popular women of the time, including courtesans, and were cherished much like idol photographs are today.

A famous example is Utagawa Sadahide’s “Contest of Beauties,” a vibrant portrayal of courtesans from Yoshiwara, Edo’s famous pleasure district.

Utagawa Sadahide, “Contest of Beauties”

Another well-known work is Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “Ume no Sakigake” (The First Blossoms of Spring). Each print depicts women chatting beneath blossoming plum trees in winter. At the Ibasen Ukiyo-e Museum in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, all three prints of this series are on display.

Because bijin-ga functioned much like idol photos, many people purchased only the prints featuring women they liked.

That is why it is rare to find all three prints of “Ume no Sakigake” displayed together, as at the Ibasen Ukiyo-e Museum.

Plum Blossom Beauties is also held by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and is recognized as a work of significant cultural value.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, “Ume no Sakigake” (The First Blossoms of Spring)

Yakusha-e

Yakusha-e are portraits of kabuki actors who enjoyed great popularity at the time. Like modern-day celebrity photos sold as merchandise, they were treasured by fans.

Along with bijin-ga, yakusha-e form one of the signature genres of ukiyo-e.

But what makes them fascinating is that they were more than simple portraits of famous actors.

Utagawa Toyokuni, “Uchiwa-e: Anonymous”

Take Utagawa Toyokuni’s “Uchiwa-e: Anonymous,” for example. Even if the depiction wasn’t strictly realistic, viewers could often identify the actor by the patterns on his haori (jacket).

Some even noticed details such as the women’s obi draped casually over the folding screen on the right, interpreting it as a hint that the actor was secretly visiting a lover.

For townspeople of Edo, part of the fun was decoding these subtle details hidden within the artwork.

Fūkeiga

Landscapes, or fūkeiga, are another key genre of ukiyo-e. The most famous example is Katsushika Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji”

Its compositions and use of color were revolutionary, elevating Japanese landscape prints to a new level of artistic prestige.

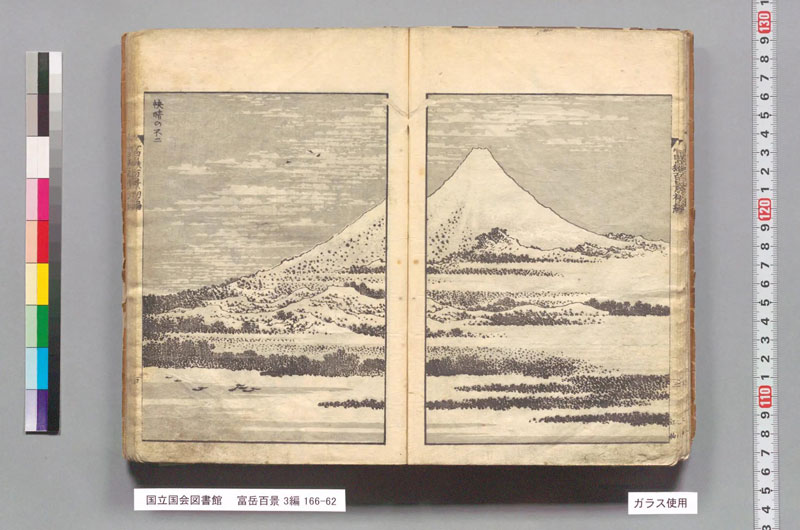

Hokusai also created “One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji,” another outstanding series focused on the same theme.

Katsushika Hokusai, “One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, Vol. 3” / Source: National Diet Library “NDL Image Bank”

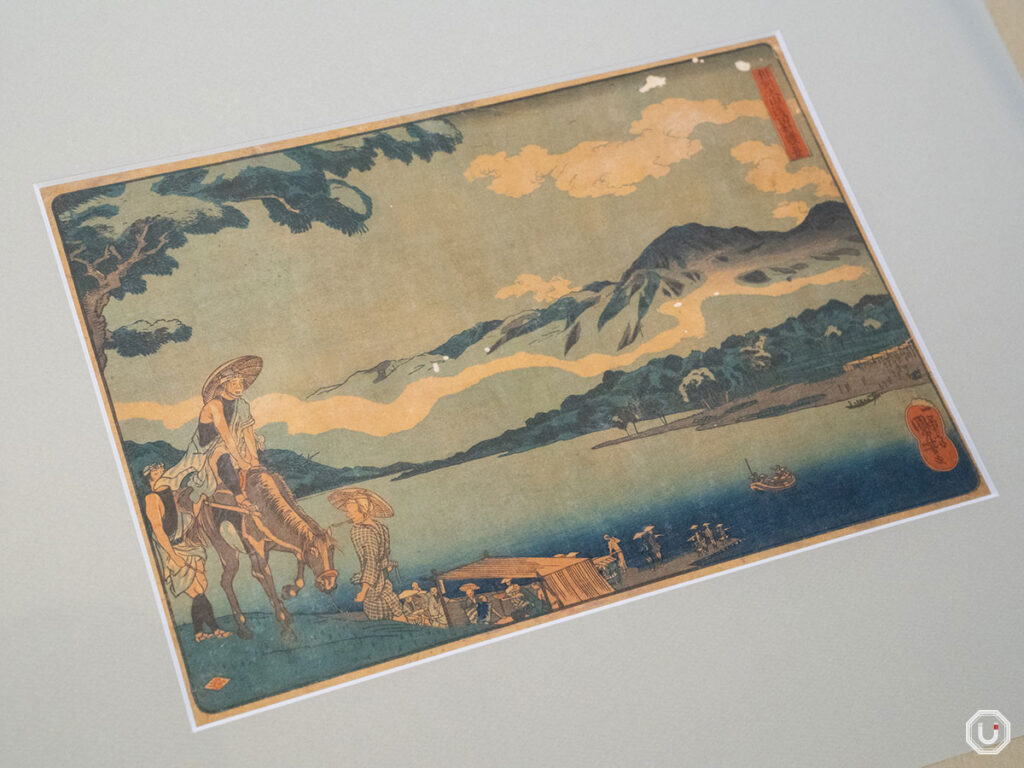

Another masterpiece of ukiyo-e landscapes is Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “View of Tamurabashi on the Ōyama Road in Sagami Province.”

With their distinctive compositions, landscape prints are a genre that continues to attract a devoted following.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, “View of Tamurabashi on the Ōyama Road in Sagami Province”

Fūzoku-ga

Fūzoku-ga, or genre scenes, depict the everyday lives of common people—such as individuals enjoying tobacco. They offer a vivid window into how people in the Edo period lived, serving today as invaluable historical records.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, “New Year’s Musical Performance at the Inner Palace”

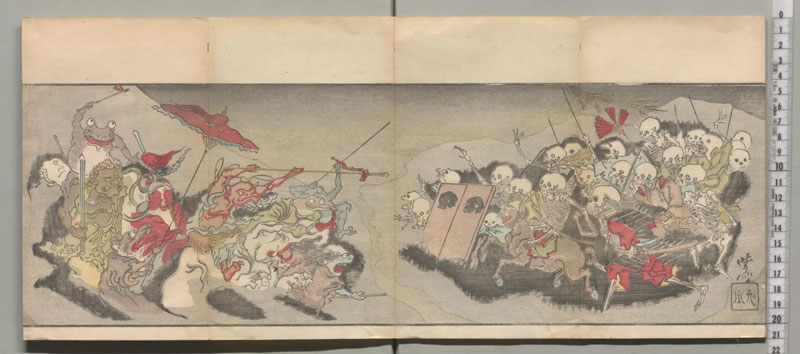

Giga and yōkai-ga (Caricatures and Supernatural Prints)

Caricatures and depictions of yōkai (supernatural beings)—known as giga and yōkai-ga—enjoyed a devoted fan base in their day, and today their influence extends far beyond ukiyo-e, appearing on merchandise and clothing designs.

Kawanabe Kyōsai, “Illustrated Discussion of a Hundred Yōkai by Kyōsai” / Source: National Diet Library “NDL Image Bank”

Kawanabe Kyōsai, celebrated for his extraordinary range of works, also produced numerous caricatures and yokai-themed prints that won him worldwide acclaim.

These works often carried a satirical edge, using exaggeration and distortion for comic effect. Like the actor prints, part of their appeal lay in interpreting the hidden intentions behind the imagery.

Five masters of Ukiyo-e

No account of ukiyo-e history would be complete without mentioning Hishikawa Moronobu. Active in the late 17th century, he was a pioneer who used woodblock techniques to establish ukiyo-e as a cornerstone of popular culture. His name invariably appears among the greats.

His celebrated Beauty Looking Back remains beloved today for its soft expression and refined composition.

From the mid-Edo period through the end of the shogunate, countless artists brought their unique styles and innovations, greatly expanding the possibilities of ukiyo-e.

Here, we’ll introduce five other artists—besides Hishikawa Moronobu—whose contributions are indispensable in the story of ukiyo-e.

- Kitagawa Utamaro: A master of bijin-ga , celebrated for his delicate depictions of feminine expressions and gestures. His best-known work is Three Beauties of the Kansei Era, which contrasts the distinct charms of three different women.

- Tōshūsai Sharaku: A mysterious artist who created around 140 works in just ten months before vanishing without a trace. His most famous piece, “Ōtani Oniji III as Edobei,” is noted for its striking facial expression and bold composition.

- Katsushika Hokusai: Internationally acclaimed for his landscapes, including the iconic Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. Said to have continued creating until the age of 90, Hokusai also became famous for changing his artist name more than 30 times throughout his life.

- Utagawa Hiroshige: Known for his lyrical landscape style, distinct from Hokusai’s. His series “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō,” comprising 55 works depicting the post towns from Edo to Kyoto, beautifully captures both the journey and the natural scenery.

- Utagawa Kuniyoshi: Popular across multiple genres, including warrior prints, satirical works, and depictions of yokai. Representative works such as “The Haunted Old Palace at Sōma” and “Graffiti on the Storehouse Wall” showcase his humor and remarkable skill.

As the unique styles of these renowned artists overlapped and evolved, ukiyo-e matured into a fully developed artistic form.

Today, ukiyo-e is highly valued in museums both in Japan and abroad, serving as a cultural treasure that conveys the aesthetics and daily life of Edo to the present day.

Each print embodies more than just an image—it vividly preserves the reality and spirit of the people who once lived it.