When visiting Japan, you’ll naturally want to experience its seasonal landscapes and traditional culture—but don’t overlook the vibrant drinking scene found in local bars and izakaya gastropubs.

From the iconic “kanpai” (cheers!) that kicks off a night out, to thoughtfully paired drinks with meals, to convenient canned cocktails from the nearest convenience store—alcohol in Japan is as much about connection and culture as it is about flavor.

Japan also offers a fascinating regional variety of alcoholic drinks, including shōchū, sake, and craft beer, each with unique local characteristics depending on where you travel.

In this guide, we’ll introduce seven types of Japanese alcoholic beverages you should try while traveling in Japan.

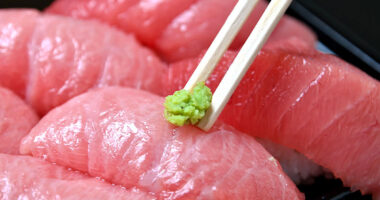

Photo for illustrative purposes

- Chūhai and sours: must-try unique Japanese alcoholic beverages

- Highballs: The Japanese twist on whisky and soda

- Japanese craft beer: brews highlighting regional ingredients and character

- Umeshu: Sweet and easy-to-drink Japanese plum wine

- Hoppy: a unique beer-like drink beloved in retro Tokyo

- Japanese sake: a rice-based brew reflecting Japan’s seasons and traditions

- Shochu: a distilled spirit from Kyūshū with deep local roots

- Where to drink classic Japanese alcoholic beverages in Japan

Chūhai and sours: must-try unique Japanese alcoholic beverages

You’ll frequently see chūhai (short for shochu highball) and sour drinks on the menu at Japanese bars, and while the names differ, they’re nearly identical in preparation. Both are typically made by mixing shochu or vodka with soda water, fruit juice, or tea.

Although the names may vary depending on the shop or region, they are generally used to mean the same thing. In other words, both are terms that represent Japan’s unique “mixed-drink culture.”

Lemon sour

Among the most popular options are lemon sours and grapefruit sours.

These drinks are made by adding citrus juice and finishing with fizzy soda for a refreshing taste. The balance of tanginess and carbonation is perfect, especially on hot summer days.

Next are oolong hai and ryokucha hai, which are made by mixing shochu with oolong tea or green tea. These skip the carbonation and offer a mellow, relaxing flavor thanks to the harmony between the tea’s aroma and the smoothness of shochu.

Both chuhais and sours can vary widely in flavor depending on the ingredients and how they’re mixed—that freedom to customize is part of their charm.

Japan’s “mixed-drink culture” reflects this sense of playfulness and ease.

These drinks are also widely available in canned form at convenience stores, making them an easy way to explore Japan’s alcohol culture.

Oolong hai

Highballs: The Japanese twist on whisky and soda

In Japan, a “highball” refers specifically to a simple cocktail made by mixing whiskey with soda water.

While this style of drinking is widely known overseas, it has evolved uniquely in Japan and is enjoyed as a staple cocktail both in bars and at home.

Japanese highball

One reason behind the highball boom in Japan is the high quality of domestic whisky.

For example, the highball made with Suntory’s “Kakubin”—known affectionately as “Kaku-High”—is fragrant and crisp, pairing perfectly with fried foods or yakitori. It’s also excellent as a mealtime drink.

At Japanese bars and specialty shops, you can even enjoy luxurious highballs made with single malt whiskies like “Yamazaki” or “Hakushu.”

Yamazaki whisky

The whisky’s delicate aroma gently expands with the carbonation, softening the alcohol’s strength while still delivering full flavor.

The key lies in balancing the sharp fizz of the soda with the aroma of the whisky.

The Japanese way of making a highball is to fill a glass with plenty of ice, pour in the whisky, and then gently add the soda last.

Rather than being flashy, Japan’s highball shines through its minimalist elegance—blending seamlessly into everyday life.

It’s an easygoing drink, and the flavor changes depending on the whisky and how it’s made. The more you learn about highballs, the more you’ll be drawn to their charm.

Japanese craft beer: brews highlighting regional ingredients and character

The charm of craft beer lies in its regional uniqueness and the brewer’s personal touch.

Small breweries are scattered across Japan, each producing its own distinctive styles of beer.

Especially worth noting are the craft beers that use ingredients unique to Japan.

Japanese craft beer

Each brewery showcases its own personality—whether it’s a white ale brewed with fragrant yuzu peel, or a craft beer featuring subtle bitterness and spice from matcha or sanshō (Japanese pepper).

Japanese craft beer goes beyond the definition of “local beer”—it has become a true expression of regional culture.

Its flavor can shift depending on food pairings, and tasting local craft beer while traveling is sure to spark your culinary curiosity.

In addition to classic lagers, explore a variety of styles like IPAs, pale ales, and saisons to find your favorite. Chances are, you’ll discover a uniquely Japanese brew that suits your palate.

Umeshu: Sweet and easy-to-drink Japanese plum wine

Umeshu, long beloved in Japanese households, is a fruit liqueur made by steeping green ume plums with rock sugar and alcohol such as white liquor or shochu. In English, it’s often referred to as Japanese plum wine.

It’s known for its syrupy sweetness and balanced tartness, making it easy to enjoy—even for those who aren’t fond of strong alcohol.

Its taste is almost dessert-like. As you sip, the aroma of ume gently spreads, leaving behind a soft, sweet finish.

Umeshu

It’s great served chilled and straight from the fridge, but the most popular way to enjoy it is on the rocks.

Pouring it over ice softens the sweetness and enhances the flavor of the ume.

Perfect as an aperitif or for relaxing after a meal, umeshu captures the essence of Japanese seasonality and the natural richness of fruit.

Hoppy: a unique beer-like drink beloved in retro Tokyo

In Tokyo’s old neighborhoods like Asakusa and Ueno, there’s a beloved local drink known as “Hoppy.”

It’s made by mixing shochu with a carbonated malt-based beverage—also called “Hoppy”—which you combine yourself at the table.

It tastes similar to beer but has a lower alcohol content. It’s also low in calories and sugar, making it a great option for health-conscious drinkers or those on a diet.

Another appeal of Hoppy is that you can adjust the amount of shochu to suit your taste or mood, giving you control over how strong your drink is.

Hoppy comes in two varieties: “White” and “Black.” These names reflect not only the color but also the flavor profile. “White Hoppy” is light and crisp, pairing well with almost any meal.

On the other hand, “Black Hoppy” has a richer, toastier flavor with subtle sweetness from the malt.

There’s even a traditional way to enjoy it.

Typically, a bottle of Hoppy is served alongside a glass or mug already filled with shochu. You pour the Hoppy in yourself—that’s the standard style.

Hoppy

The glass of shochu is called the “naka” (inside), and you pour the Hoppy into it to create your preferred strength. One bottle of Hoppy usually makes 2 to 3 drinks, so it’s common to just order more “naka” when refilling.

When ordering, you typically say “naka okawari” (refill the inside) if you want more shochu, or “soto okawari” (refill the outside) if you want just more Hoppy.

Sipping from a glass in a retro-style tavern that still holds the atmosphere of the Showa era feels like stepping into the daily life of Tokyo’s downtown locals.

If you want to experience a side of Tokyo not found in tourist guides, Hoppy might just be your perfect introduction.

Japanese sake: a rice-based brew reflecting Japan’s seasons and traditions

When talking about Japanese cuisine, sake is an essential part of the conversation.

This traditional fermented beverage, made from rice, water, rice kōji, a beneficial rice mold used in fermentation, pairs surprisingly well with Japanese cuisine, which emphasizes the natural flavor of ingredients.

Just one sip reveals the sweetness and umami of the rice—and even the character of the region where it was brewed.

Sake

Famous sake-producing regions include Niigata, Yamagata, Akita, and Fukushima—all located in Japan’s Tohoku region.

With harsh winters, pure snowmelt water, and high-quality rice, Tohoku has long been a thriving area for sake brewing.

Each region has its own character, making sake-tasting feel like a journey through Japan.

Sake comes in several types, with flavor profiles that change depending on the rice polishing ratio (seimai buai) and brewing methods. Among the many varieties, these are four of the best-known categories.

Daiginjō-shu: Brewed with rice polished down to 50% or less. It’s slowly fermented at low temperatures, resulting in an elegant aroma and delicate taste—ideal for fragrance lovers.

Ginjō-shu: Polished to 60% or less. This type is slightly lighter, well-balanced, and easy to drink.

Junmai-shu: Made with only rice and water. It’s full-bodied, pairs well with meals, and allows you to savor the full flavor of the rice.

Honjōzō-shu: Made with rice, water, and koji, plus a small amount of distilled alcohol, which creates a light, clean finish and smooth drinkability.

While sake is often enjoyed chilled, it can also be gently warmed or served hot depending on the season—each temperature offering a new expression of flavor.

Pair it with local cuisine, and you’ll discover an even deeper connection to Japan’s four seasons and regional culture.

Shochu: a distilled spirit from Kyūshū with deep local roots

Shochu is a distilled spirit widely loved throughout Japan’s southern Kyūshū region.

Unlike sake, which is brewed, shochu is distilled—giving it a clean, crisp finish that makes it an excellent companion to food. It also offers a wide variety of ways to enjoy it.

The most distinctive feature of shochu is how dramatically its flavor changes depending on the base ingredient. The three most common types are:

Imo Jōchū (Sweet Potato): Made from satsuma-imo (Japanese sweet potatoes), this variety is known for its rich aroma and deep, earthy flavor. Its bold scent can be quite addictive. Kagoshima and Miyazaki are especially known for this type.

Mugi Jochu (Barley): Primarily produced in northern Kyushu, especially Oita, it has a lighter profile with a toasty aroma that pairs perfectly with grilled fish and fried foods.

Kome Jochu (Rice): Commonly made in Kumamoto, this mellow and gentle shochu is a versatile match for all kinds of Japanese cuisine.

In some regions, you’ll also find unique variations like shiso (perilla leaf) or brown sugar shochu.

Encountering these local specialty spirits is part of the joy of travel in Japan. Discovering which type of shochu is tied to which region is often a delightful surprise that enhances the journey.

Shochu

There are many ways to drink shochu: diluted with water, on the rocks, with hot water, or mixed with soda—each offering a different experience.

Sweet potato shochu is especially aromatic when mixed with hot water, while barley shochu becomes crisper when served on the rocks.

In summer, a soda mix offers refreshment; in winter, a hot mix provides cozy warmth. Shochu’s adaptability makes it perfect for savoring the seasons.

Despite its slightly higher alcohol content, many shochu varieties contain zero sugar and zero purines, making them a popular option for health-conscious drinkers.

Alongside sake, shochu is a cornerstone of Japan’s drinking culture. Especially when traveling through Kyushu, don’t miss the chance to pair local shochu with regional dishes.

Shochu on the rocks

Where to drink classic Japanese alcoholic beverages in Japan

If you want to truly dive into Japan’s drinking culture, be sure to visit izakaya (Japanese-style pubs) and tachinomi (standing bars).

These casual spots, where locals and tourists often sit elbow-to-elbow over drinks, are packed with the charm of Japanese food and drink culture.

Yakitori Marukin in Shinjuku, known for its wide selection of alcohol

At izakaya, you’ll find a wide variety of classic alcoholic drinks—from chuhai and highballs to regional craft beers and carefully crafted umeshu.

Paired with small dishes like yakitori or sashimi, these drinks offer a deeper taste of the local flavor and culture.

Enjoy a wide selection of drinks alongside hearty dishes at “Butaya Toriyama” in Shimbashi

Many establishments also offer an extensive selection of sake and shochu from across Japan, making it a real treat to compare regional varieties.

On the other hand, standing bars offer a more casual atmosphere. With just a narrow counter between you and the owner, it’s easy to strike up a conversation, and even strangers often find themselves chatting like old friends. Sipping on down-to-earth drinks like Hoppy or chuhai, you can enjoy a small taste of the extraordinary in everyday life.

Sample a wide variety of sake in standing-bar style at “Tachinomi Kuri”

Japanese alcohol reflects the climate, culture, and craftsmanship of each region. A drink encountered during your travels can offer a deeper understanding of the place itself.

So don’t just savor the taste—immerse yourself in the stories behind each sip, and enjoy the rich world of Japanese drinking culture.