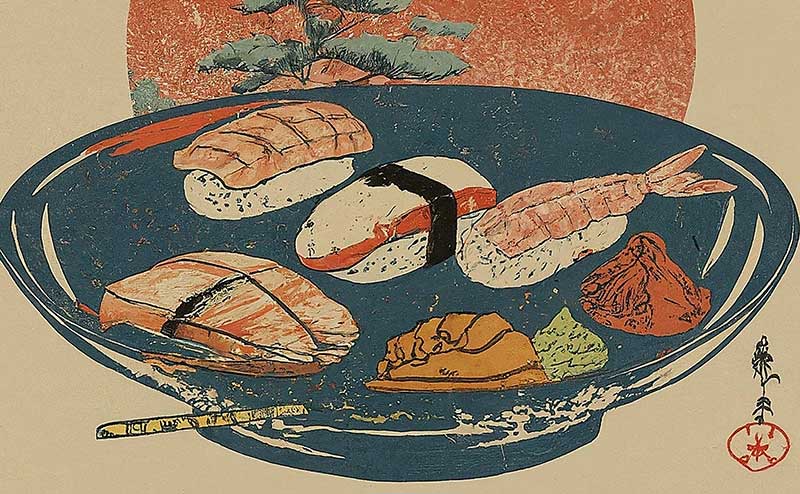

Sushi, celebrated worldwide as a hallmark of Japanese cuisine, is more than a meal—it’s a cultural experience in its own right.

The exquisite harmony of vinegared rice and fresh seafood reflects craft honed over centuries and a distinctly Japanese sense of aesthetics. For travelers considering a trip to Japan, tasting authentic sushi offers a rare chance to feel the depth of Japanese culture first-hand.

This article offers a comprehensive introduction to Japan’s sushi culture—from historical background to today’s many ways to enjoy it—plus practical manners and tips for choosing restaurants that every visitor should know.

“Tsunesushi” serving “Maguro Nigiri”

Sushi history and cultural background

Japanese sushi has undergone a long evolution to reach the form we know today. Its roots are widely understood to lie in ancient preserved fish known as narezushi, with fermentation-based techniques believed to have arrived in Japan via broader East and Southeast Asia. The path from there to modern nigiri-zushi (hand-pressed sushi) mirrors broader shifts in Japan’s food culture.

From narezushi to hayazushi

The oldest style, narezushi, was a preserved food made by fermenting fish with salt and rice. This history as a fermented food shows that sushi is not merely a dish but a crystallization of Japanese ingenuity and technique. From the Heian period (794–1185) through the Muromachi period (1336–1573), hayazushi (a “quick” style of sushi) emerged with shortened fermentation, and techniques using vinegar to add acidity were established. Thanks to this innovation, sushi became a food enjoyed by many more people.

The birth of nigiri-zushi in the Edo period

In the late Edo period, the prototype of today’s nigiri-zushi was born. Edo-style sushi, widely credited to chef Hanaya Yōhei for popularizing it, took the simple yet innovative form of placing fresh seafood on vinegared rice. With the advent of Edomae-zushi (Edo-style sushi), sushi fundamentally shifted from preserved fare to “fresh food enjoyed on the spot.” Because it used seafood caught in Edo Bay (now Tokyo Bay), it came to be called “Edomae,” a name still synonymous with top-quality sushi today.

Photo for illustrative purposes

Significance as part of washoku heritage

In 2013, washoku (Japanese food) was inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list (officially listed as “Traditional Dietary Cultures of the Japanese”). While UNESCO recognized washoku as a whole rather than specific dishes, sushi is often cited as an emblematic expression of those values—seasonality, respect for ingredients, and craftsmanship. For international visitors, savoring sushi is a cultural encounter with Japan’s aesthetics and spirit.

Washoku (photo for illustrative purposes)

Varieties of sushi and what makes them special

Japan’s sushi culture has diversified across regions and eras, and today there is a remarkable range to enjoy. Each style has its own character, offering different flavors and experiences.

Nigiri-zushi (hand-pressed sushi)

Nigiri-zushi is the most traditional and formal style, with the chef forming each piece by hand, sometimes right in front of you. The instant when shari (seasoned rice)—gently warmed in the sushi chef’s hands—and fresh neta (topping) become one in your mouth is the very essence of Japan’s sushi culture.

Flavor varies by fish type, cut, and degree of maturation; even the same fish changes with the seasons in fat content and texture. At high-end counters, an omakase (chef’s choice) progression is typical—often starting with lean cuts of tuna, then white fish, silver-skinned fish, and shellfish—letting you fully appreciate the chef’s skill and sensibility.

“KINKA sushi bar izakaya Roppongi” serving “SALMON OSHIZUSHI”

Maki-zushi and its many styles

Maki-zushi (rolled sushi) wraps rice and fillings in nori seaweed and stands alongside nigiri as a representative style. From thick rolls to thin rolls and temaki (hand rolls), each format has its own pleasures and ways to eat.

“Tsunesushi” serving Tekka-maki (tuna roll) as part of the Tokujō Nigiri set

Rolls are beloved for the way nori and multiple fillings mingle at once—a style that showcases Japanese creativity. They’re popular at conveyor-belt shops too and have inspired creative and fusion styles such as the California roll.

“SUSHI Gonpachi Nishi-Azabu” serving the “Dragon Roll”

Regional sushi traditions

Distinct regional styles across Japan reflect local cultures and ingredients, offering unique expressions of sushi.

In Kansai, oshi-zushi (pressed sushi), made by compressing ingredients in a wooden mold, is prized for its beautiful appearance and dense flavor. For celebrations, chirashi-zushi (scattered sushi) is known for its vibrant, festive presentation and is a favorite in home cooking as well.

| Type | Key features | What to look for |

|---|---|---|

| Nigiri-zushi | Edomae sushi tradition, hand-crafted by the chef before your eyes | Conversation with the chef; watching the technique |

| Maki-zushi | Seaweed-wrapped, easy to enjoy | Harmony of multiple fillings |

| Oshi-zushi | Kansai style, pressed in a wooden mold | Elegant look and concentrated flavor |

| Chirashi-zushi | Colorful dish often for celebrations | Seasonality and festive presentation |

“Tsukiji Sushiiwa Tsukijishiten” serving their “Bara Chirashi” (limited quantity)

Types of sushi restaurants and dining styles

Japan’s sushi venues vary widely by price point and service style, each offering a distinct experience. Visitors can choose the right fit based on budget and the kind of meal they want.

Top counters for a premium experience

At high-end counters, you can converse directly with the chef while enjoying each piece.

Watching the chef’s hands up close as pieces are served one by one elevates sushi to the level of culinary art. The omakase format is standard, with the chef selecting the very best seasonal items. Reservations are often required and prices are higher, but it’s a rare chance to experience the pinnacle of sushi culture in Japan.

Chefs may share stories about sourcing and mastery of techniques, turning the meal into a cultural experience that goes beyond eating.

Hiroshi Uehara, the third-generation owner “Tsunesushi”

Kaiten-zushi: casual and varied

Kaiten-zushi (conveyor-belt sushi) is a uniquely Japanese system that lets you sample many styles with ease.

Plate colors indicate prices in an easy-to-understand system, which is great for guests who may not speak Japanese. With plates starting around 100 JPY at some places, it’s ideal for beginners who want to try many items or travelers on a budget.

Many modern conveyor-belt shops offer tablet ordering and automated delivery lanes—a fun taste of Japanese technology and efficiency.

“Magurobito Akihabara” serving their Red Sea Bream, Salmon Avocado Mayonnaise, and Toro Takuan Roll

Convenience stores and supermarkets

Japan’s convenience stores and supermarkets sell surprisingly high-quality sushi at reasonable prices.

It’s handy for a quick bite during your trip or a meal back at your hotel—and a great way to appreciate Japan’s food technology. In the morning you’ll often find freshly made options with careful presentation.

Sushi at a Japanese supermarket (photo for illustrative purposes)

Manners and how to order for the best experience

Understanding a few basics will deepen your appreciation and help you experience Japanese hospitality more fully.

Ordering and communicating at premium counters

At high-end establishments, ordering omakase is common. Oftentimes, you can share your budget and the chef will compose the best meal within it.

Conversation is part of the experience—asking about sourcing or preparation deepens your understanding and satisfaction. Counter seats let you watch traditional techniques up close. Ask permission before taking photos, and be mindful of the chef and other guests.

“Sushi Ginza Onodera SOUHONTEN” serving 15 types of sushi from their “Seasonal Omakase Nigiri Course: Tsuki”

How to eat politely

As a general rule—especially at high-end counters—dip a small amount of soy sauce on the topping side and avoid soaking the rice. Customs can be more relaxed at casual spots like conveyor-belt shops.

Eating with either hands or chopsticks is acceptable—choose what feels comfortable. Gari (sweet pickled ginger) is a palate cleanser; eating a little between different pieces helps you taste each one more clearly. Ideally, enjoy each piece in one bite so rice and topping come together perfectly in your mouth.

Seasoning sushi topping with soy sauce at “Tsukiji Sushiiwa Tsukijishiten”

Making the most of kaiten-zushi

At conveyor-belt shops, you can take plates from the lane and also use tablet ordering, when available.

Popular items are best grabbed early; special requests can be placed via the tablet or by asking staff. Stacking finished plates is common, and at checkout, a staff member counts them to total your bill.

An Umami bites writer enjoying kaiten-zushi at “Magurobito Akihabara”

What defines quality: the craft behind great sushi

Top-tier sushi quality comes from multiple elements working in harmony. Understanding them helps you taste more deeply and better appreciate Japanese food culture.

Shari: how it’s made and why it matters

Shari is one of the most important factors in sushi quality.

Every step shows the chef’s skill and experience—the rice variety, cooking method, vinegar blend, and temperature management—so the same topping can taste completely different. At high-level shops, the rice is kept about body temperature to harmonize with the neta. Each shop guards its own vinegar blend; the balance of sweetness, acidity, and saltiness defines the house style.

At “Sushi Ginza Onodera SOUHONTEN,” the rice is seasoned with aged akazu (red vinegar)

Selecting toppings and maturation

Choosing premium seafood is one of a sushi chef’s core skills. At the market, chefs judge clarity of the eyes, color of the gills, and firmness of the flesh to select the very best. Especially for white fish, proper maturation increases umami, yielding a depth of flavor distinct from standard sashimi. Mastering this takes years; optimal methods and timing vary by species, season, and size.

Passing down traditional technique

Training takes years; many chefs apprentice for a long time before going solo. Grip pressure, rice amount, and pairings with neta all affect the final flavor, so continual practice and experience are essential. This traditional apprenticeship reflects an important side of Japanese culture, passing along etiquette and spirit as well as technique.

A chef at “Sushi Ginza Onodera SOUHONTEN” forming nigiri

Toward a more sustainable sushi culture

Today, the sushi world is paying increasing attention to marine conservation and sustainable fisheries. Through responsible consumption, many efforts aim to pass delicious sushi on to future generations.

MSC certification and responsible sourcing

MSC (Marine Stewardship Council) certification is an international standard for seafood from sustainable fisheries. Some sushi chains are now using MSC-certified seafood as part of their environmental initiatives, reflecting growing concern for ocean health. These efforts look ahead to the future of sushi culture.

Partnering with local fisheries

More restaurants are working directly with local fishers to secure a steady supply of fresh, high-quality seafood. This supports regional economies and helps build a more sustainable food culture. Knowing about these initiatives can make a traveler’s dining experience more meaningful.

Fisheries at work (photo for illustrative purposes)

What travelers can do

Travelers can also contribute to sustainable sushi culture.

Choose seasonal seafood, try regional styles, and support restaurants that care about the environment. These choices deepen your trip’s meaning and your understanding of Japanese food culture.

Photo for illustrative purposes

Summary

Japanese sushi is a cultural jewel forged by long history and tradition, offering an experience that goes beyond a simple meal. From its beginnings in narezushi to the evolution of Edomae, from diverse types and regional styles to the skill and spirit behind each piece—sushi speaks to the depth of Japanese culture.

On your visit, consider enjoying sushi step by step: casual convenience-store lunches, the variety at kaiten-zushi, and finally the peak experience at a premium counter. By learning basic manners and engaging with chefs, you’ll gain respect for the ingredients and insight into the craft—making your meal even more rewarding.

Efforts toward sustainability are also advancing. Sushi is a cultural experience for all five senses, enriching your trip to Japan. Through authentic sushi, discover the heart of Japanese food culture.